A Step-by-Step Guide to Stock Market Investing

A couple of caveats before we begin. First of all, do not take this as financial advice. Each individual has different circumstances and different risk tolerances. A strategy that is right for me might keep you awake at night. Secondly, I don’t claim to be an expert. I’ve been investing actively in the stock market as a full-time job for 5 years, which is hardly long enough to be an authority, but I have managed on average to beat the stock market indices by a good 10% a year since I started. I’ve also had enough people ask me how they can do the same and I think it’s time I gave some kind of answer. A full answer can’t of course be given in a blog post. This post is intended more as a map, so that if you have the inclination you can go out and get the information you need in order to invest well.

At the outset you should know that broadly speaking there are two types of investors. Active and passive. If you’re an Australian and you have a superannuation fund you’re already a passive investor. A good percentage of your super is being invested by someone else in both the Australian and international stock markets. An active investor is one who goes out and buys individual stocks. As we’ll see later on, only a small percentage of people have the combination of time, temperament and ability to be successful as active investors.

Step 1: A cash surplus

The very first thing you need in order to buy shares is some spare cash. Now you might have $1,000, $10,000 or $100,000. Actually it doesn’t really matter what you have right now, as long as you start. Perhaps you have nothing to invest though. Maybe you’re in debt. In that case the first step is to take a look at your monthly budget and try to make some tweaks so that you have some leftover money each month. Even if it’s just $100 at first. When you realise the power of investing over time you may be inspired to making significant lifestyle changes like swapping your Mercedes for a Toyota, moving back with Mum and Dad for a couple of years and going on a camping trip instead of going to Egypt to see the Pyramids. In all of this there is an element of deferred gratification. To what extent you economise is up to you. But you have to decide at some point whether you’re forever going to be the kid that presses that button and gets one cookie, or the one that waits and gets two. By the way with investing you don’t just get two cookies. You get 4, 8, 16, 32… but it does all depend on a certain level of discipline and sacrifice in the beginning.

Step 2: Understand the rate of return concept

Most of us know about the rate of return from when we borrow money from the bank. Let’s say you borrow $500,000 to buy a house, the bank might ask you to pay 5% interest on that loan. Now look at it from the bank’s point of view, they are making a 5% return on their investment. The banks money is bound up in your house for a certain period of time. They charge you 5% for the use of that money because there’s a certain level of risk that you’ll default on that loan. If you do though they can seize your home and sell it and get their money back. Home loan interest rates tend to be quite low compared to other kinds of loans because generally speaking people pay back home loans. In addition the underlying security, your house, generally maintains its value. There are situations where home values fall though, and that’s why banks insist on some kind of a buffer, say for example a 10% deposit in cash. Therefore even if the value of your home goes down by 10%, the bank can still get their money back.

Now let’s flip it, you loan your money to the bank for 2 years. One bank offers you 5% and the other offers you 5.5%, where will you park your money? Clearly if both banks are equally reputable, you’ll park it for 5.5%.

This percentage that you can expect annually on your investment is the rate of return. In traditional finance it is said that when the level of risk in your investment increases, so should the return that you receive for taking on that risk. If you look at the average return of the US stock market for example, it sits somewhere around 8% per annum over the long term. Now that 3% difference between stocks and a bank deposit doesn’t seem like all that much, but when you compound that amount for years and decades the end result is massively different.

Let’s take the example of someone who invests $100,000 for 25 years. If they receive a return of 5%, 8% , 15% or 20% annually this is what they will end up with respectively:

5%: $338,635

8%: $684,848

15%: $3,292,345

20%: $9,540,000

As you can see, being able to invest at a higher rate of return can mean the difference between living month to month forever, or becoming quite wealthy over time. Now admittedly achieving a 20% return for 25 years is a tall order, in fact only a handful of people in the world have achieved that, like Warren Buffett.

The rate of return concept is a key lens from which to view your finances. For example do you leave that $10,000 in your cash account, or do you keep $2,000 in there and put the $8,000 into a savings account where you make 3.5%. Or do you take that $8,000 and pay off your credit card debt which is costing you 16% a year. All of these little decisions matter and add up to a big difference in the end.

Here’s a decision I was faced with, do you try and pay off the debt on your house as quickly as possible and reduce the time you’re paying that 5% interest, or do you use that money to create a stock portfolio. My house was appreciating at 1-2% per year after costs and inflation and my stock portfolio has made 7%, 26% or even 31% in a year. In the end I sold my house and deployed all the capital in the stock market, that’s not the right approach for everyone, but it was for me.

Also keep inflation in mind, if the bank offers you 5% on your deposit, you need to account for inflation. The latest figure in Australia was 3.8%. So actually after inflation you’re making 1.2% on your money. Which… isn’t great.

Step 3: Passive investing

In Australia we have this great system called superannuation. It allows workers to put aside a portion of their income which is taxed at a lower rate, into a fund that invests that money for them until retirement. The US has their own equivalent called the 401k. These are examples of passive investing. And if you’re prepared to wait until retirement to access your money they are probably the most tax effective way of passively investing in the stock market.

If you want more flexibility you can also start your own passive investing pool by investing in index funds. There are various kinds of index funds, what they do is buy a collection of stocks and when you buy that index fund you own a small piece of 100 or 200 stocks. The index funds ‘track’ particular categories of stocks, for example the top 500 US companies or the top 200 Australian companies.

Once you have found a couple of indexes that you want to invest in, you could for example just buy a little bit each month and gradually build up your position. The key here is to keep buying periodically, especially when the stock market is down. I would also avoid fad indexes like the ‘AI 125 fund’ or ‘Renewable growth fund’, made up names but you’ll come across a lot of junk like this. These tend to underperform the broader market in my experience as the fad dies and attention shifts to somewhere else. Instead stick to funds as mentioned that track the whole stock market of a country or group of countries.

Most people can probably stop here. But if you have the attributes listed in the next step, then you may consider doing what it takes to craft yourself into a decent active investor.

Step 4: The active investor, what does it take?

It would be nice wouldn’t it, you invest your money at 30, make 15-20% a year on it and by the time you’re 55 you have tens of millions. And it is absolutely possible, but here comes the reality check, it’s also extremely difficult. Here is what I think you need to make it as an active investor:

Time: Realistically you need to set aside 1-2 hours a day to work on this. And most active investors who are successful over the long term spend more like 5-6 hours a day. Up until recently I was probably spending 6-8 hours a day on activities related to my investments. The good news is after you get over the initial learning curve you can dial it back. But either way, we’re talking about a significant investment of time, over a period of many years. Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hour rule certainly applies to stock picking.

Learning machine: Investing is a multi dimensional discipline, everything you have learnt can come into play and help you to make the right decision at the right time. The more angles you have from which to look at something, the better the chance that you’ll decide correctly. You have to keep in mind that every time you buy or sell a stock there is someone on the other end of the transaction who has the opposite view to you. The one who has the most information and the best judgement will make the right call. Every well-known successful investor shares this trait; they read and read and read. So if you are eternally curious, have a pile of books on your bedside table and another on your coffee table, becoming an active investor could be a good fit for you.

Long term view: The best investments play out over 5, 10 or even 25 years. Do you have the patience to wait? And as mentioned earlier, are you able to forgo the use of $10,000 now for it to grow into $1,000,000 later on.

Calm under pressure: Unlike putting your money into a term deposit, when investing in the stock market you are bound to encounter volatility. You need to have the stomach to sit back and watch a portfolio that was one day worth $100,000 be worth $80,000 if it’s a bad year. And once every few decades it may get beat down even more than that. If you’re not prepared to ride out these periods, active investing is probably not for you.

Numbers: You don’t need to be a math genius, but there’s no getting around it, investing is about numbers. I’m only average with numbers and I get by, but if they totally freak you out, again active investing may not be for you. So some degree of numerical fluency is required.

Good judgement: This one is hard to quantify and I’m not sure where it comes from. If I had to guess it would be that good judgement comes from exposure, either in person or via books, to a lot of other people with good judgement. Probably that and life experience. Then again even those who are well read and experienced aren’t guaranteed to have good judgement. So perhaps to some extent this is innate. In the investment context good judgement means being able to absorb as much information about a particular investment and then making some kind of educated guess about how things will turn out, or to decide whether your view is different to the markets, therefore creating a buying (or selling) opportunity. One thing to keep in mind is you don’t need to be right all the time, nobody is, you just need to be right more often than you’re wrong.

Step 5: Feed the beast

So you’ve gone through the above list and you tick most if not all the boxes and decide that you’re going to give active investing a go. The next step is to build a foundational layer of knowledge from which to make decisions. I call this feeding the beast. Ideally you have an almost unquenchable thirst for learning and down that gullet you begin to pour in investment related information. The more you absorb, the better you’ll be able to identify trends and make sound calls. You want to grow that Chihuahua into a financial Doberman. Here is what I did:

Business and accounting knowledge: If you studied something else at uni then you can educate yourself on the fundamentals of business, marketing, accounting, management. All are important but for investing purposes you really need to know the basics of accounting. I have to admit I find accounting boring as hell and if you asked me whether a particular transaction is a debit or credit and how it affects each accounting statement I couldn’t tell you. Nevertheless I’ve done my best to learn and I know what to look for in accounting statements.

Read the financial news daily: The papers that I recommend are the Financial Times (London) and The Australian Financial Review. Even if you just did this routinely, you’d start to put together a lot of information about geopolitics, tax and companies. This is critical because a lot of your investment ideas can come from reading the news. It also gives you the ability to identify global trends over time.

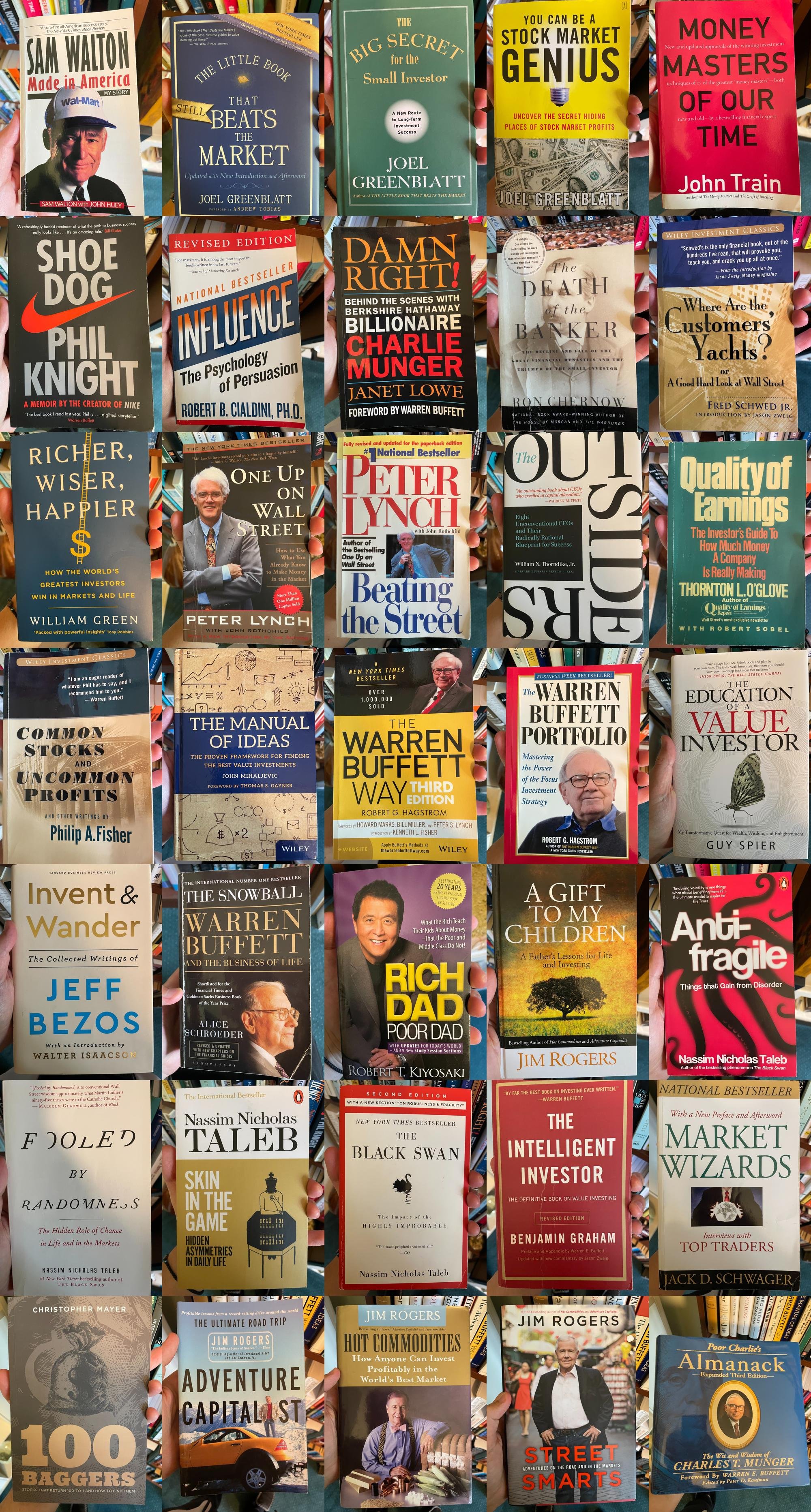

Investment books: you don’t need to study finance formally, actually I think you can learn more by reading the right books. We are very fortunate in that some of the best investors in the world have written extensively about their process. A lot of the time it’s not easy reading, but the information is out there. At the end of this post I’ll attach an image of some books to get you started. Keep in mind that reading in other disciplines such as history and science is also very useful and will make you a better investor.

Company annual and quarterly reports: They can be pretty dry and tedious to go through, but there’s no avoiding this step if you want to pick stocks. These reports are available on a listed companies corporate website. They include a presentation of a company’s financial reports and management commentary on the reporting period. As you get practised at reading these reports you’ll begin to pick out subtleties, how confident is management feeling, how much fluff vs substance is there in the reporting, to what extent is management shareholder focused vs focused on lining their own pockets. All the reading you’ve done in the above steps will help you to interpret what you’re seeing in company reports.

X (Twitter): A largely overlooked resource especially by traditional finance types is X. I find it invaluable. X gives you the ability to tap into the thought of some of the great current investors. Many of them post daily, and you can see what they are thinking, for free! The trick with X is that there’s also a lot of noise, so it relies on you having a good filter. If you get caught up in narrative it may do more harm than good. Then again if you get caught up in narrative without looking at the more subtle underlying causes, you probably won’t make it as an investor anyway.

Step 6: Buy an individual stock

This is where the rubber meets the road. You’ve loaded up on investing knowledge and now you actually have to pick a stock. In its essence you’re looking for a stock that for whatever reason is mis-priced. In other words the market is pessimistic about the future of this company, and you are optimistic. But where does the investment idea come from in the first place? It might come from reading a news article, it may come from reading an X post, it might come from a friend or it might come from looking at the products and services you use on a daily basis.

Once you have your idea, it’s time to go for a deep dive into that company. I usually start with annual reports. I’ll read the latest report cover to cover. Then you could look back at the last few years of annual reports and see how things have developed. Of course I’ll pour over the company’s website. I want to see what they’re about, what is their ethos, what is important to them. Then I’ll look at the market in which they operate, do they have competition? What about the country in which they operate, do I really want to own a mine in Myanmar? ( I did and lost all my money in that investment when the military took over)

Then I’ll look at the media, is there any coverage, and are people talking about them on X? These come last because I already want to have formed my own opinion. If everything lines up and I’m confident that the stock is cheaper than it should be, I’ll buy.

Step 7: Hold

You’ve done all the hard work, now comes the part where most people fail. You need to hold that investment long enough for the rest of the market to catch up with your analysis. If you’re right, eventually that stock will re-price to a fairer level. But it takes time! It can take a year or two for the market to catch on. I think holding on for a year is an absolute minimum, unless something changes that affects the outlook for that company materially. When the stock price does start moving up again don’t give in to the impulse to sell and book some profit. In fact if you’ve chosen the stock well, there’s really no reason to sell unless the fortunes of the company change. The big money in investing is made by picking the right stock and holding it for many years.

I’ll have to leave it there. This is already too long for a blog post. Each of these topics could be broken down and discussed in much more detail, which they are in the books that are pictured below. I encourage you to read those books if you’re keen on picking stocks for yourself. If you have any questions or comments please reach out to me over X or on Instagram. I wish you all the best on your investing journey and I hope that in time it gives you the financial freedom to enjoy life to the fullest.

Traian